Shucking Virginia oysters (Ostreidae Crassostrea virginica) in a colonial kitchen. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

The brick-built Dutch colonial fort on Flag Island, Guyana, 1968. (Photo, Charles H. Kable.)

Dutch glass bottles and an enigmatic brown stoneware jar found on Flag Island by diamond prospectors. H. of jar 5 3/4". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Dutch and English bottles recovered from Flag Island along with the brown stoneware oyster jar illustrated in fig. 5, which bears an impressed inscription for Manhattan oysterman Daniel Johnson. (Courtesy, Susan Williams; photo, Robert Hunter.)

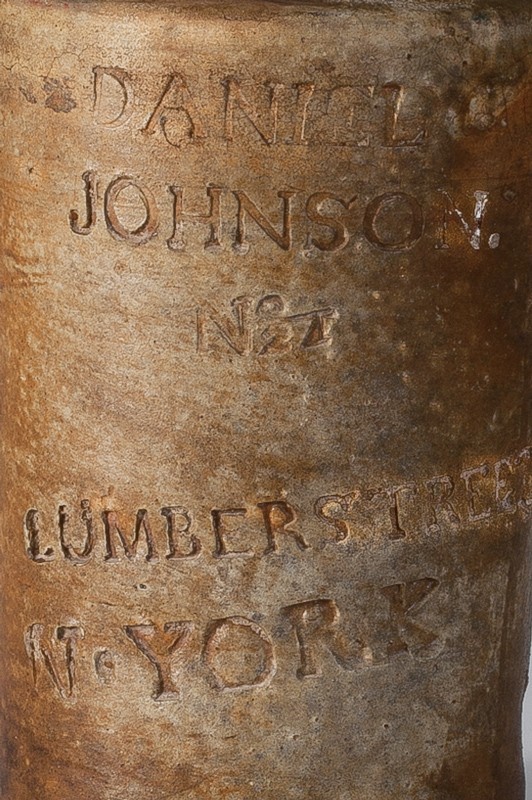

Detail of the oyster jar illustrated in fig. 4, attributed to Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1800–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". Impressed on side: DANIEL / JOHNSON / NO. 24 LUMBER STREET / N. YORK.

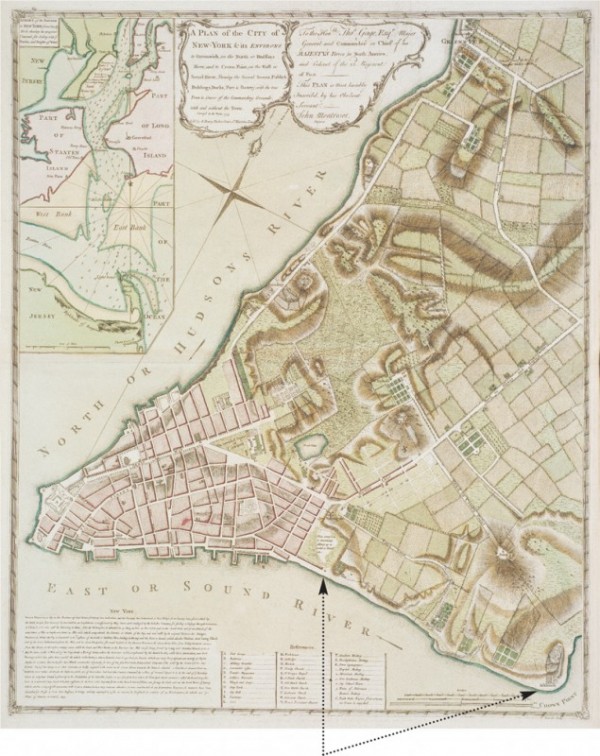

John Montresor, A Plan of the City of New-York & Its Environs to Greenwich, on the North or Hudsons River, and to Crown Point, on the East or Sound River, Shewing the Several Streets, Publick Buildings, Docks, Fort & Battery, with the True Form & Course of the Commanding Grounds, with and without the Town, London, England, 1767 (this copy reissued in 1775), 25 3/8" x 20 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Daniel Johnson’s workplace would have faced the East River within the area marked “This overflow is continually filling up in order to Build on.” In the lower right corner of the map, the property marked “Acklands” is the approximate site of Thomas Commeraw’s later stoneware factory. By 1800 the curve identified by the British as Crown Point would return to its old Dutch name of Corlears Hook.

John Bachmann, Bird’s Eye View of New York and Environs, 1865. 31" x 46". Published by Kimmel & Forster, New York. Corlears Hook is being pointed to by the steamship emerging from the inlet at right. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

Members of the Kable family bargaining for bottles in Guyana, 1968. (Photo, Charles H. Kable.)

Oysters jars, attributed to Thomas Commeraw, ca. 1800–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". Left jar impressed on side, DANIEL JOHNSON AND CO. 24 / LUMBER STREET / N·YORK.; right jar impressed on side, BROWN / WATER STREET / N·YORK. (Courtesy, Brandt Zipp, The Thomas Commershaw Project/Cocker Farm, Inc.; photos, Luke Zipp.) The jar on the right was made for William Brown, who was still in business as an oysterman ca. 1810. The history of these jars is unknown, but it is reasonable to suppose that both came from the Guyana source, possibly part of a combined shipment.

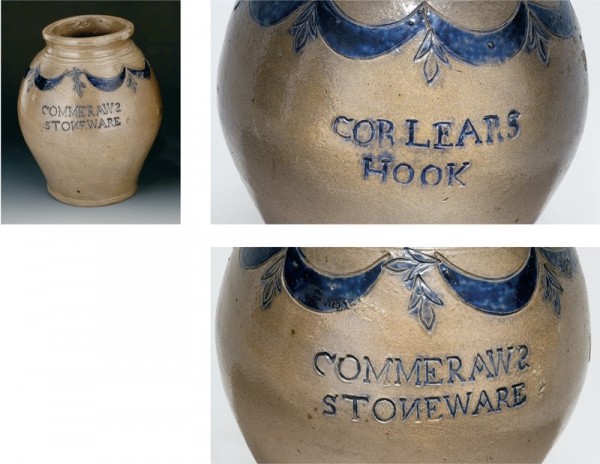

Storage jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1797–1798. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 15/16". Impressed on one side, COMMERAWS / STONEWARE; impressed on the other side, CORLEARS / HOOK. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Oyster jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1800–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 3/4". Impressed on side, DANIEL / JOHNSON.NO24 / LUMBERSTREE / N.YORK. (Courtesy, New York State Museum.) This jar from Thomas Commeraw’s Corlears Hook pottery was acquired by the New York State Museum in 1905, the same year that Corlears Hook Park was laid out.

Oyster jar, American, probably New England, mid-nineteenth century. Black-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) This jar has a recessed lid opening, similar to those of the earlier Commeraw jars.

Oyster jar and a lid, London, England, mid-nineteenth century. Bristol-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". Impressed on jar, IMPERIAL / POTTERIES · STEPHEN GREEN · LAMBETH; impressed on lid, SINGER / VAUXHALL / LONDON REGISTERED NO.4138 DEC 17 1858. D. 3 1/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jar was found in New England and the lid in a Virginia field.

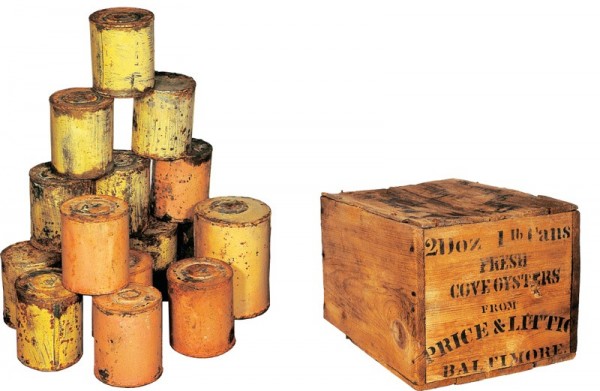

Baltimore wooden shipping crate and its tinplate oyster cans from the 1856 wreck of the steamboat Arabia in the Missouri River. Known as cap-hole cans, these vessels were sealed with solder. (Courtesy, David Hawley, Arabia Steamboat Museum.)

In 1967 two American adventurers prospecting for diamonds in Guyana’s backcountry highlands were encouraged by local officials to abandon their project and leave the country. On their way out, the men traveled down to the mouth of the Essequibo River and came to an island variously known as Flag or Fort Island (fig. 2).[1] On it stand the ruins of an eighteenth-century Dutch fort, and in the island’s muddy pits and ditches the men found large numbers of Dutch and French glass bottles which they proceeded to salvage and surreptitiously ship to the United States. The bottles were then sold to antique dealers, restoration projects, and collectors up and down the East Coast, some of the purchasers exhibiting or selling them as English—which they were not. Nevertheless, for many years thereafter the influx of these bottles and their availability at modest prices inadvertently ruined the market for genuine eighteenth-century English bottles.

When the prospectors arrived at my door, I bought a representative number and, in appreciation, the sellers gave me a brown stoneware jar of a shape I had never before encountered (fig. 3). As they did not know what it was, they said it had no marketable value.[2] I was pleased to agree with them, and the jar went into my stoneware collection to be brought out whenever a stoneware specialist happened by. One said that he thought it might have been an acoustic jar, often used by the Spanish in the arches and ceilings of churches, but no confirming documentation was forthcoming. Someone else thought it might be a container for oysters, but he, too, was unable to prove it. Consequently, the jar went onto a back shelf and was almost forgotten until I received a letter of inquiry from Susan Williams of Springfield, Virginia. She enclosed a photograph of three Dutch wine bottles and a stoneware jar almost identical to mine, found in 1968 by her brother buried in mud beside the river at Fort Island (fig. 4). She asked, “How old might it be and what was it used for?”

Although Susan was unaware of it, she had the answer and I did not. Her cylindrical stoneware jar is stamp-inscribed “DANIEL JOHNSON / NO 24 / LUMBER STREET / N.YORK” (fig. 5). When I told her that the town was almost certainly New York and not York in England, she immediately set to work searching the city directories and soon found that in Manhattan in 1796 there were two Lumber Streets as well as a Daniel Johnston living at 1 Lumber Street, his trade given as “oysterman.”[3] Assuming that Johnston was a misspelling of Johnson, that seemed to settle the matter—until it was found that the 1799 directory lists both Daniel Johnson and Daniel Johnston. The former is listed at an unnumbered address on Lumber Street; the latter at 276 Water Street and his trade given as “oysterstand.”[4] Taking this information at face value one might conclude that Johnston was not an oyster fisherman but the proprietor of a “small often open-air structure for a small retail business.”[5] However, in the 1800 directory Johnson is listed at both 24 Lumber Street and 276 Water Street. Thus, it seems his primary address is confirmed, while the Water Street number puts him in the same building as Daniel Johnston. It makes much more sense, therefore, to conclude that the name is misspelled in both the 1796 and 1799 directories, that Johnson and Johnston are one and the same, and that he lived on Lumber Street and had his fresh oyster stand at 276 Water Street.[6]

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Manhattan was rapidly expanding along the East River in the direction of Corlears Hook (figs. 6, 7). Why Johnson’s address was unnumbered in the 1799 directory and given as No. 24 a year later is unknown, but taking street-name changes into account, it is probable that Johnson’s jar was made no later than 1804.

The 1800 directory puts Johnson where his jar says he belongs, but in the 1804–1805 directory he is listed at both 24 Lombard Street (its name before becoming Lumber) and 106 Cherry Street.[7] The transition from Lumber to Lombard—and then Lombardy—was almost certainly due to problems of pronunciation. To New York oystermen who had never heard of the medieval Lombards, Lumber was easier to say and remember. Although the 1804 New-York Register showed Daniel Johnson on Lombard Street, its name was not officially changed to Lombardy until 1809.[8] A city directory (Low’s) of 1807 warned that “care should be taken to understand the difference of the spelling of Lombardy and Lumber, as the want of attention to this has led many strangers astray.” To this one can only add “Amen.”

However, the thought serves as a useful segue to the Manhattan Trinity Church records, which show that on June 9, 1793, a Daniel Johnson married Phillis Dickson,[9] and that on August 10, 1805, a Phillis Johnson married John Edwards, whose race was cited as Negro. If, as seems likely, this was the same Phillis who twelve years earlier had married Daniel, it follows that he, too, was an African-American. But was he the Daniel of the oyster jar? There had been yellow fever outbreaks in New York in 1802 and 1805. The distinguished African-American scholar Ralph Ellison cited an example from the 4th Ward: “Out of the 458 blacks, living in 10 cellars, 33 were sick, of whom 14 died, while out of 120 whites, living immediately over their heads in the apartments of the same houses, not one even had the fever.”[10]

It is important to note that the United States Federal Census was designed to identify the white population and so was divided into columns that recorded the ages of both “Free White Males” and “Free White Females.” At the end of each line was space for “All Other Free Persons” and for “Slaves.” To be a free black householder was an anomaly calling for an unspecified citation. In 1800 a Daniel Johnston living in Ward 7 was identified by name as “a Black” who answered for four more in the “other Free Persons” column. Ten years later there was a Daniel Johnston, “a Black” in Ward 4 who had five “free persons” in his household or business. The increase from four to five strongly suggests that this was the same person—that is, Johnson of the jars who had moved from one ward to the other. That implies, too, that Johnson was relatively prosperous and employed four and then five African-Americans to work his boat and shuck his oysters.

On another page of the 7th Ward Census, property occupier (or owner?) Thomas Commeraw also bore the suffix “a Black.” It is significant, however, that he was the only individual so identified in a page of forty names. More on him anon.

Only from the census records can we be sure of a New Yorker’s race; but although the more frequent directories do not so state, their inclusion of laborers, maids, cartmen, coachmen, and the like renders it safe to assume that many were people of color. By 1810 there were 7,470 free blacks in New York City, and social historian Shane White has stated that the presence of blacks “was most noticeable in the oyster trade, which they dominated.”[11] In 1810 the official census listed twenty-seven oystermen, of whom sixteen were black. Five years earlier Longworth’s Trade Directory listed only fifteen, among them “Johnson Daniel” and “Johnson John.”[12] That increase in the number of oystermen belies the evidence that the dumping of waste into New York Harbor had been ruining the oystering business.[13]

The New York ward system had been set up in 1683, the 4th Ward being one of the original six. By 1800 there were twenty-two wards; the 7th was located east of Catherine Street, an area subject to rapid expansion in the first decades of the new century. That may explain why Daniel was at 1 Lumber in 1796 (the first dwelling built?) and Lumber—with no number—three years later. He may have been an early beneficiary of that urban growth. By 1804 his home address had been changed to 24 Lombard Street, and he had left his oyster stand at 276 Water Street and gone to 106 Cherry Street. The directory for 1810 lists only the Cherry Street address. If, as seems likely, the “stand” had been Johnson’s, it may be that he was dead and his well-established trade was being continued there in his name.

With Johnson located and possibly dead by the summer of 1805, the next question focuses on his jars and where they were made.[14] Were they English or American? As ceramics made in England for the American market were sometimes inscribed, it might be that a New York importer placed a custom order with an English manufacturer on Johnson’s behalf. In 1763, for example, James Gilliland was established on nearby Wall Street as an importer of china, glass, and earthenware. However, one doubts that a briney-handed oysterman would have patronized a high-end importer. It is far more likely that he would have gone to the edge of the city to an earthenware potter like Jonathan Durell, who in 1775 had advertised that he made “butter, water, pickle and oyster pots, porringers and milkpans. . . .”[15]

Durell’s linking of pickle and oyster pots indicates that one shape could be used for either—or both. However, another Durell ad published two years earlier suggested that pickles and oyster pots were not necessarily related. There he was selling “butter, water, pickle, oyster and chamber pots.”[16] The moral, therefore, is that one should not read too much into the placement of a comma.

A much earlier advertisement, printed in England in 1708, lists “right Ground Oysters pickled to be sold by the Pot for 2s there being 25 large oysters in the Pot.”[17] By the mid-eighteenth century Swedish traveler Peter Kalm visited New York and described two methods for pickling oysters, the simplest as follows: “They are taken out of the shells fried in butter, put into a glass or earthen vessel with melted butter over them, so they are fully covered with it and no air can get to them. Oysters prepared in this manner have likewise an agreeable taste, and are exported to the West Indies and other parts.”[18] But buttered or in brine, by the mid-eighteenth century pickled oysters were being shipped from New York to the West Indies. Fresh oysters, by contrast, had a relatively short shelf life and were sent in bags and barrels to Boston and elsewhere on the American mainland.

In 1774 mercenary army captain John Gabriel Stedman, then stationed in Suriname in neighboring Guyana, wrote in his journal that he had received from “Mrs. Gordon 3 bottles English muskat, a cask of Boston biscuits, and a small keg of oysters.”[19] He did not say whether they were fresh or pickled, but since he mentioned a keg one must assume that he meant a small wooden barrel and not a stoneware jar.

Jars like Johnson’s were of a distinctive shape, being wide-mouthed and having a recessed collarlike orifice, presumably to take a flush-fitting stoneware lid. Most of the bottle and jar “treasures” from the mud around Fort Island were salvaged by local children, and it is highly unlikely that anyone told them that these flat discs had any value and were worth retrieving.

Susan Williams recalls her sister-in-law telling her that most of the bottles were recovered by children probing the mud with sticks. After discovering that foreigners would pay real money for the glass bottles the children or their parents started selling them to tourists in Georgetown (fig. 8). When the locals heard that saleable bottles were being found on the island, they hurried there to buy more. How many oyster jars were recovered and sold before the trove ran out is anybody’s guess. Two more were auctioned by Crocker Farm, Inc., in November 2005, one bearing the inscription “DANIEL / JOHNSON. AND CO. 24 / LUMBER STREET / N·YORK,” the other “BROWN / WATER STREET / N·YORK” (fig. 9). Unfortunately, for confidentiality reasons the auctioneers declined to reveal who bought them (and, more important, who sold them),[20] but it is reasonable to deduce that these, too, came from the mud of Fort Island, the inference being that they were part of a single shipment. To support that thesis it is necessary to determine whether Brown was in business prior to 1804. He was. In 1799 he was an oysterman at 15 Ann Street, although by 1810 he had moved to 128 Water Street and 48 Nassau Street.[21] As previously noted, Daniel Johnson/Johnston was operating on Lumber Street as early as 1796, and soon thereafter (ca. 1800) he was buying jars bearing his name as the sole proprietor. The “AND CO.” marked on the second Johnson jar suggests an expansion of his business and that the two jars are of successive dates, probably between circa 1800 and 1805. Although such business designations are recorded as early as the mid-eighteenth century, they were rare until well into the nineteenth. Johnson’s usage, therefore, implies that he was literate and a possessor of more education than one might expect of an oysterman.

The only recent book devoted to oyster containers is Jim and Vivian Karsnitz’s Oyster Cans, whose title means what it says; the book focuses almost exclusively on the tin-plated cylinders known first as canisters. The authors attributed the introduction of food-preserving containers to a Frenchman, Nicholas Appert, who in 1809 used glass bottles. By 1840, because glass containers were so easily broken, we are told that they were replaced by cylindrical tin cans whose entry and dispensing apertures could be sealed with solder. Known as “cap-hole cans,” they so closely resemble Johnson’s stoneware cylinders there is every reason to contend that in America the design evolved directly from ceramic to metal without the intrusion of glass.[22] Indeed, the Guyana brown stoneware cylinders can claim to be the earliest examples of oyster jars yet recorded, be they in stoneware, glass, or tin.[23]

The previously cited Jonathan Durell was a relative newcomer. The German stoneware-potting families of Crolius and Remmey had been in business on the edge of town as early as 1728 and continued through several generations.[24] In 1800, still in the area known as Pot Baker’s Hill, John Remmey II sold his premises to his brother John Remmey III, and John Crolius sold his to his son Clarkson. There is no direct proof that either factory made Daniel Johnson’s jars, but there is some evidence of a connection, albeit slight. By the end of the eighteenth century these two families are known to have marked their better products using block stamps assembled from printer’s type. Clarkson Crolius stamped his “C. CROLIUS / MANUFACTURER / MANHATTAN-WELLS / NEW YORK”; on many surviving examples John Remmey used the same address, but he occasionally marked his wares “J. REMMEY / MANHATTAN-WELLS / N.YORK.”[25] The city abbreviation, therefore, parallels the usage found on Johnson’s oyster jar. But jumping to conclusions can be a dangerous sport. Another stoneware potter, Thomas Commeraw, long thought also to be of European descent, was working in New York City between 1793 and 1812. He, too, stamped his name and business address on his wares: “COMMERAWS / STONEWARE / CORLEARS / HOOK” (fig. 10).[26]

As it turns out, Commeraw was a prominent figure in the black congregation known as the African Church in the City of New-York. On June 2, 1809, he led the singing at a service heralding the abolition of the slave trade.[27] In the 1800 census he was listed as “Thomas Commeraw, Black.”[28] There is little doubt that he was a free African-American, one of many who inhabited lower Manhattan at the beginning of the nineteenth century. His name, possibly an anglicized version of Commerau, suggests that he was of French origin. If he was, he might have been among the hundreds of French refugees who fled from Santo Domingo (Haiti) at the time of Pierre Toussaint’s great slave rebellion of 1791.

Corlears Hook, as Commeraw would have known it, offered a small patch of high ground amid a marsh which, in the precolonial centuries was inhabited by the Lenape Indians. Through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the marsh was gradually filled in with trash from slaughterhouses and boatyards. However, a map of 1766–1767 shows the high area at the hook—labeled Ackland—laid out and occupied.[29] By 1789 there were three unidentified buildings on the site (see fig. 6).[30] In 1803 a plan was developed by architects Mangin and Goerck to straighten out the East River shoreline to turn the hook into a corner.[31] The plan was rejected, but another of 1811 by surveyor John Randel Jr. proposed a similar straightening of the shoreline.[32] The Manhattan City Commissioners adopted the Randel plan, and through the 1820s the topography of New York was drastically changed, the hills behind the hook being flattened and their soil dumped as fill into ponds and marshes. It is likely that the site of Commeraw’s factory had long been buried by the time that construction of the Corlears Hook Park was completed in 1905.

Most of Commeraw’s marked wares are jugs of various sizes and usually include the word STONEWARE with the “N” in reverse, although the “N” in N. York is correctly applied. No reversed “N” is present on the Johnson oyster jars. That potentially negative evidence is refuted by the fact that Commeraw was using block-set inscriptions to promote his one-off wares, whereas Johnson’s, being a special order, would have had the letters set individually and thus avoid Commeraw’s signature mistake.[33] Commeraw’s named wares are cobalt-decorated and include ovoid devices that some call “bow knobs” but others see as “clam shells.” Either way, Thomas Commeraw’s Corlears Hook factory products are readily identifiable.

Before it became a park, Corlears Hook was a promontory at the north end of Water and Cherry Streets, much closer to Daniel Johnson’s business than to the Crolius/Remmey kilns, and the waterfront was ideally located for Johnson to transport his jars by water or on a wagon down Cherry Street.

At some date prior to January 1906, the New York State Museum acquired a Daniel Johnson oyster jar recorded as “having the shape of a tobacco or snuff jar” (fig. 11).[34] Its condition prompted the cataloger to speculate that Daniel Johnson himself might have been a potter. The publication date of the museum’s acquisition suggests that the jar was found in 1905. It may be no coincidence, then, that construction of the Corlears Hook Park was completed in that year.

In sum, it is reasonable to deduce that at some date between 1800 and 1804 one or more Commeraw craftsmen impressed N·YORK on the oyster jar that in 1967 was retrieved from Guyana’s Fort Island. With Daniel Johnson’s race established, it seems likely that he ordered his jars from a factory where his needs were most readily understood. If true, the oyster jars are historically important evidence of free-black entrepreneurship in the last days of slavery in New York City.

Throughout the nineteenth century, ceramic jars continued to be sold as shipping containers for oysters, but as the Karsnitzes’ book Oyster Cans demonstrates, “cap-hole” cans were losing favor against heavily black-glazed stoneware made in either Maine or New Hampshire.[35] These had straight necks and were sealed with corks, their principal characteristic being an internal black glaze that extended over the neck and down to a point below the shoulder. Beneath were printed the names of proprietors such as the C. C. Porter Fish Company of Maine or E. T. Wilson of Farmington, New Hampshire. A similar black glaze covers both the inside and outside of a jar of the “cap-hole” variety that might be a transitional example from the second quarter of the nineteenth century (fig. 12).[36]

Another jar from New England claiming to be an oyster jar was imported from England; it is Bristol-glazed and has bead-and-reel rouletting at the shoulder and a square-cut rim (fig. 13). It carries the impressed mark of Stephen Green’s Imperial Pottery in Lambeth and therefore dates prior to 1858.[37] Similar jars from other London-area factories were described as being covered for “pickling and preserving.” Several patents were registered for the airtight sealing of such jars. The illustrated example found in a Virginia field was patented by Alfred Singer of Vauxhall on December 17, 1858 (fig. 13, right). Designed to twist and lock, the lid fitted a wider version of the Stephen Green jar.[38] In 1873 Doulton and Watts of Lambeth were selling similar shapes as “Air-tight Covered Jars.” Doulton’s nearby competitor James Stiff was offering comparable jars and illustrated them with a metal clamp over the lids. In neither case did the manufacturers define these jars as containers for oysters.[39] However, an example in Oyster Cans is print-identified as being made for the Café Royal’s Oyster Bar at 17 West Register Street in Edinburgh.[40] Other oyster jars in white stoneware and with less readily sealed mouths were made for one Thomas Anderson of Glasgow in the late nineteenth century.[41]

By the mid-nineteenth century, brown stoneware cap-hole oyster jars like those made for Daniel Johnson were being copied in tin. An intact crate of the cylindrical cans was found in the wreck of the steamboat Arabia, which sank in the Missouri River in 1856. The crate bore the stenciled information “2 Doz 1lb Cans/ FRESH / COVE OYSTERS/ FROM / PRICE & LITTIC / BALTIMORE” (fig. 14).[42]

The decline of the specifically defined cap-hole oyster jar forced potteries to seek a wider market by advertising these jars as all-purpose containers. Consequently, unless the jars carry printed labels, their evolution through the latter years of the nineteenth century is hard to define. There is no doubt, however, that African-American Thomas Commeraw’s stonewares were at the fountainhead of an ongoing oyster distribution industry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to Susan Williams for bringing her jar to my attention and for leading the charge in the research that led to this article. I am grateful, too, to Brandt Zipp of Crocker Farm Stoneware Auction for sharing his study of Thomas Commeraw and his Corlears Hook factory, and to Dr. Shane White in Sydney, Australia, for his help sorting out elusive, nineteenth-century Manhattan addresses. Finally, my thanks to Christine Annan at Edinburgh’s Café Royal Oyster Bar.

Guyana had been a Dutch colony from 1616 until ceded to Britain in 1814, whereupon it was renamed British Guiana. It secured its independence in 1966. The neighboring Dutch Guiana (Suriname) gained independence in 1975.

In 2005 an American auction house sold two at $3,500 each.

One was in the 3rd Ward on the Hudson River (North River) side. The other was in the 7th Ward on the East River. Immediately above his listing was a Richard Johnston, who was cited as a potter on Magazine Street.

Longworth’s American Almanack, New-York Register and City Directory (New York, 1799), pp. 262–63.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition (2001), s.v. “stand.”

New York historians have long recognized that the “responsibility for public record-keeping often fell to people with relatively little formal education.” Gilbert Tauber, comp., “A Guide to Former Street Names in Manhattan” (2005), available online at www.oldstreets.com (accessed July 29, 2011). Ceramic historian Brandt Zipp independently came to the same conclusion after locating the Lumber Street addresses of the people flanking Johnston in the 1800 Federal Census.

Previously one of the two Lumber Streets, this one was earlier known as Rutgers Street and subsequently (in 1831) changed to Monroe Street.

Tauber, comp., “Guide to Former Street Names in Manhattan.” Lombardy became Monroe Street in 1831. The phonetically induced connection is amplified by the 1810 directory listing Ephraim Whitlock at No. 32 of nearby Oliver Street and identifying him as “inspector of lumber.” The New-York Directory for 1810 still had people living on Lumber Street.

Trinity Church Parish Registers, June 9, 1793, and August 10, 1805. The minister who performed both ceremonies was Benjamin Moore, who five years later found himself in trouble for officiating at the marriage of a slave. Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770–1810 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), p. 89, citing Daily Advertiser, July 25, 1798.

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (New York: Random House, 1952), p. 9, citing a contemporary medical report.

White, Somewhat More Independent, pp. 161, p. 236 n. 34.

The 1804 directory has a John Johnson, oysterman, living at 92 Warren Street in Ward 5, which could indicate that Daniel and John were not related. (It should be remembered that while census records identified African-Americans, the city directories did not.)

Mark Kurlansky, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007), p. 121.

That assumption may have been scuttled by Longworth’s Directory, which lists Daniel Johnson as still alive at 106 Cherry Street in 1810, having been at both at 106 Cherry and 24 Lombard in 1804.

Rita Susswein Gottesman, ed., The Arts and Crafts in New York: Advertisements and News Items from New York City Newspapers, vol. 1, 1726–1776 (New York: Printed for the New-York Historical Society, 1938), p. 85.

The New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, March 15, 1773.

Nancy Cox and Karin Dannehl, eds., Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550–1820 (University of Wolverhampton, 2007), www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=739 (accessed July 28, 2011).

Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, p. 73, citing Peter Kalm, Travels in North America, vol. 1, 1747–1748, edited by Adolph B. Benson (New York: Dover Publications, 1966).

The Journal of John Gabriel Stedman, 1744–1797, Soldier and Author, Including an Authentic Account of His Expedition to Suranam in 1772, edited by Stanbury Thompson (London: Mitre Press, 1962), p. 147.

Auction house owner Brandt Zipp recalls that both jars came together from a dealer in Canada.

Ann Street and Nassau Street were in Ward 2 but adjacent to Ward 4.

Jim Karsnitz and Vivian Karsnitz, Oyster Cans (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1993), p. 11 (Southern Can Co. ad, 1914). On September 6, 1856, the Arabia sank in the Missouri River and was discovered and archaeologically salvaged in 1988. Among the thousands of objects recovered was a crate of tin oyster cans with shapes similar to that of the Guyana jars. David Hawley, The Treasures of the Steamboat Arabia (Kansas City, Mo.: Arabia Steamboat Museum, 1995), p. 58.

Karsnitz and Karsnitz, Oyster Cans, p. 150. In 1922 the William Heyser Company of Baltimore was offering oysters in both “small Cans” and “Glass Jars.”

Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66.

Donald Blake Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1971), p. 48, fig. 27.

Ibid., p. 217. The name “Corlear’s Hook” dates back to the Dutch creation of Manhattan, but during the British occupation it was known as Crown Point.

The order of service and the lead speaker’s address are in the archives of the New-York Historical Society.

1800 U.S. Federal Census Record, New York Ward 7, Roll 23, p. 905, image 286. A probable relative was John Commeraw, who was married to Zerviah Cook and listed by the New England Historic Genealogy Society in 1817 as being “of colour.”

Bernard Razner’s map of 1766–1767. See Paul E. Cohen and Robert T. Augustyn, Manhattan in Maps, 1527–1995 (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1997), p. 71.

New-York Directory and Register, 1789. Cohen and Augustyn, Manhattan in Maps, p. 93.

Joseph François Mangin was an emigrant Frenchman. His partner was Casimir Goerck.

A copy of the Randel map is in the New York Public Library; another is in the Library of Congress.

There was no such error in the lettering of the BROWN / WATER STREET N.YORK jar.

59th Annual Report of the New York State Museum, 1906, pp. 28–29. The full text of this report is available online through Google Books, s.v. “59th Annual Report of the New York State Museum” (accessed July 28, 2011).

Karsnitz and Karsnitz, Oyster Cans, pp. 122–23.

This jar was purchased from a California dealer who could not identify it.

In that year Green retired and sold his business to the Fulham Pottery.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 323–25.

Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery: Excavations 1971–79, Archaeological Report No. 6 (London: English Heritage, 1999), pp. 361–68.

The Café Royal’s oyster bar opened in Edinburgh in 1826 and is still renowned for its oysters both Rockefeller and Kilpatrick. It moved to its present location in 1863. According to Christine Annan at the Café Royal, the address changed from 17 to 19 West Register Street about eight years ago.

Karsnitz and Karsnitz, Oyster Cans, p. 123.

Hawley, The Treasures from the Steamboat Arabia, p. 56.